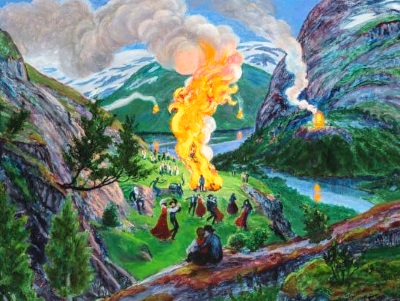

Young people want to embrace the inner connection between nature and humanity. The movement today is not trying to get away from the reality of nature and of humankind, any less than the early nineteenth century Romantic movement. Rather, young people want to experience and unveil the natural mystery at the world’s core, so as to be able to live at one with nature and to fulfill their task in the real world as protagonists of reality. It is a vigorous and pulsating life, physical and emotional, living in woods and on hilltops in mutual friendship that explores the depths of identity. Aware more than ever of their physical state, they comprehend life as determined and sustained by a spiritual force. It is to this spiritual force, permeated by the divine Spirit, that their religious ardor is dedicated.

It is a religion of this world, not the hereafter – a religion without dogma, without a priesthood, to be lived ever afresh rather than to be believed. As Friedrich Schlegel expressed it, it is the “very intimate, restless, voracious participation in all life.”[1] Just as in the romanticism of a former day, so today too, the real religious need is for this all-embracing Spirit of life. This urge to comprehend everything as a whole makes it possible, in Tieck’s words, to see through the world with the vision of a seer.[2] The whole of life, in all its diversity, is what the romanticists and the new youth seek.

This goal must place them in opposition to the false reality of random snippets of existence. No isolated bits of nature, no individual experience of the senses, no detached scientific research – none of this is capable of guiding anyone to a religious grasp of the universe; the sole and only thing that will do this is the experience of a supernatural, all-embracing Spirit. Oneness with the absolute, eternal, and infinite foundation of the world – through which matter, nature, and humanity are ruled and guided – gives to this religious attitude transcendence as well as immanence. The universal striving of today’s youth wants to see the reign of soul and spirit over the collective mass of matter, and it therefore longs for the expression of the future.

The connection of today’s youth with nature becomes a symbolic impulse towards this deepest ideal. “We have not searched for God outside of nature,” they assert, and, “We have not found him in nature”; then they continue, “But by receiving into ourselves the harmony of nature we have been led to the God within us.” The youthful person, profoundly moved by nature’s design, finds in the depths of personal emotional life that which is divine and essential, and on that basis attains an all-encompassing view of the world. It is this experience that no intellectual interpretation or research is able to bring about or explain this feeling the soul has for the world. Newborn children are full of a feeling for life, and yet are not in the least able with their intellect to investigate their life sphere. In just the same way the emotional experience of nature, which liberates the soul hitherto shut in upon itself, has nothing to do with a scientific explanation of nature and of the life of the soul.

“The fetters of the intellect have fallen,” Franz Werfel exclaims, “and my spirit is but one gigantic sentiment.”[3] The imprisonment of the soul within itself, brought about by the intellect and its logic, is broken asunder. Instead of the bloodless “I am,” the “We are” has stepped in, brimful of the Spirit of the universe. The “Thou” with which we feel united remains indeed unknown to us, yet by boundlessly rejoicing with all the sunlit life around us, and by sharing to the full all the suffering and pain in the world, the soul strives to find the God of the universe and at the same time seeks to be one with his world. The greatest and highest one longs for is to be free from one's isolation.

A religious attitude determined by Christ means affirming life just in this sense: that all the strength and vitality of the body comes to expression in work and activity among people, and in a life close to nature. The strong yearning for nature which animates our youth finds its fulfillment in Christ. Christ’s deeply felt communion with God means that he has a highly conscious relationship to God’s creation – the creation which Christ himself fills and pervades. For the first Christians there was nothing in nature which had not come into being through Christ the Logos, nothing which did not have his life (John 1:3). It was not only that Jesus ever again gazed with love at birds and flowers, at dogs and sheep, at a field and the seed sown in it, at the vine and the corn, at trees and the lake, at towns and mountains, earth and sky; not only that he used them as an everlasting picture of all religious, all-embracing truths. It was that he also opened the eyes of his people, and laid upon them the obligation to rule and possess the earth. Such a central affirmation of life, reaching down into the life of all things, can never lose itself in languid enjoyment, but means glowing dedication to life for the purpose of joyful service and intensive activity.

[1] Friedrich Schlegel, 1772--1829, was a poet, literary critic, philosopher; considered one of the early German romantics.

[2] Ludwig Tieck, 1773—1853, one of the founding fathers of the Romantic movement.

[3] Franz Werfel, 1890—1945, Austrian writer of Jewish-German-Bohemian origin. He was a spokesman for lyrical expressionism.

Draft translation.

Article edited for length and clarity. View original document in our digital archive: The Religious Sentiment of Today’s Youth.