Against the backdrop of the social unrest at the disintegration of the Weimar Republic, Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor, and rising antisemitism, Arnold’s comparison of original Christianity and the social principles of Karl Marx expresses his ideas of a Christian’s responsibility in the face of injustice. More than just a philosophical comparison, as well as a daring discussion of Marxism at a time of Nazi fed anti-communist sentiment, Arnold outlines the resistance the Bruderhof would take in the next years. The Bruderhof met the consequences of resistance to the totalitarian Nazi regime, the resulting economic hardship, and eventually in 1937, expulsion.

Marx once expressed it in a Brussels newspaper in the following words: “The social principles of Christianity preach cowardice, subordination, humility, in short all the attributes of the riffraff. But the working class needs its courage, its self-confidence, its pride, its independence, even much more than its bread. The social proletariat is revolutionary.”

The question, however, is whether Karl Marx was right in his assessment of the contrast – whether readiness for the cross and the knowledge that not human beings, but God alone, can achieve what is necessary, is to be regarded as cowardice, self-contempt, subservience, and servility. This would presuppose that Christianity is not a fighting life, but that instead, quiet, meek submission to fate is what is essentially Christian.…

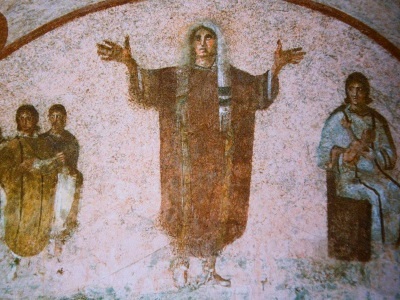

In original Christianity we find something different. Not defiance, to be sure, not violent revolt; certainly not pride and self-confidence – none of these things. So this really is a contrast to Marxism. Yet in the real, apostolic early Christianity we find a courage for the spiritual struggle that dares to take upon itself the utmost without regard for consequences when the justice of God’s kingdom is at stake.…

The difference goes still deeper, however. Early Christianity proclaims Jesus as the incarnate Word, the Son of Man, who willingly let himself be executed by the state of highest military and juristic standing, by the Jewish state of the temple with the best ecclesiastical organization, by the majority of the people – by all the things that are generally considered good.…

In the case of Karl Marx, the focus of the movement is class consciousness; it is the dispossessed class recognizing itself as such and defending itself from remaining a dispossessed class. But in apostolic Christianity, instead of class consciousness, the focus is the church; it is God’s kingdom; it is awareness that people who have come to faith live crucified and dead to themselves. Not, however, simply to acquiesce in everything, but rather to represent the cause of God’s kingdom in opposition to all the other things that surround them; to uphold the cause of the church in the face of all dangers and threats.…

One could, of course, call this innermost attitude of original Christianity a social principle. But one cannot see this social principle as cowardice, self-contempt, and servility. It was just this very principle of God’s kingdom, of the church, that enabled those first Christians to make the utmost sacrifice of death. This principle, then, is not an individual’s principle, as misunderstood by many Christians because they think redemption is a completely personal matter. Not a social principle of human beings, but of God, and a social principle of human beings only to the extent that people are called to live in this purpose and Spirit of God. Not out of their own strength but out of the power of the Spirit given to the church.…

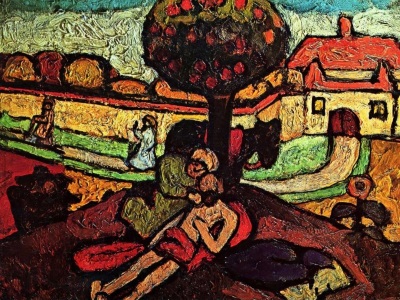

Therefore, Christians are not commanded to look on passively when their fellow human beings are enslaved, for instance. The order is not given, for example, that when warring armies invade, when people are humiliated and persecuted, Christians must simply take such circumstances upon themselves as a cross and bear them with resignation as God’s inevitable decree. We find nothing of the kind in original Christianity. Certainly Christians are obliged to suffer death on this way, to let themselves be put to death rather than to instigate violent insurrection. All the more are they challenged to combat oppression with every inner resource in the name of Jesus Christ. A Christian has the duty of standing up against all wrong with power and commission and authority. Confessing Christians must not tolerate public or private wrong for one moment without a clear protest….

We come now to the ultimate questions, and we shall once more get the following clear: the future must bring humankind its calling – which is not enslavement – and not annihilation. But has violence ever played a constructive and creative role in history? Neither in the victory of Marxism nor in the defeat of the Bolsheviks by bloody, violent suppression. The way of force is not the way of God’s heart; nor is it the way that leads to the actual leading of the Spirit.…

It is the special characteristic of the mission of Jesus Christ that it rebukes the injustice of the world and does so at the risk of death, as was the case with John the Baptist and with Jesus Christ himself. We have no need whatever here to ask how the crucifying of the proletariat could best be prevented. That is not the question to begin with. For it is not up to us at all to achieve and accomplish that. Much more, it is a question of standing at the side of the oppressed with a witness of love and truth, solidarity and fellowship. What we have here is a valuation, in this case to evaluate who is practicing injustice and who is suffering under injustice. This is what Christians are to confess to. They must see where the wrong lies.

Draft translation.

Article edited for length and clarity. View original document in our digital archive: Meeting transcript, March 21, 1933.